We

must march for academic freedom in science. In both South Africa and

Ohio I’ve had to stand up for academic freedom; for science, not

silence. It is sad that we need to do this again and again. The

short message of this post is that protests and marches can effect

change, both big and small. The longer message follows, about a

bigger change. I promise that it is worth the long read, especially

the poignant ending that can inspire us all. Minds do change.

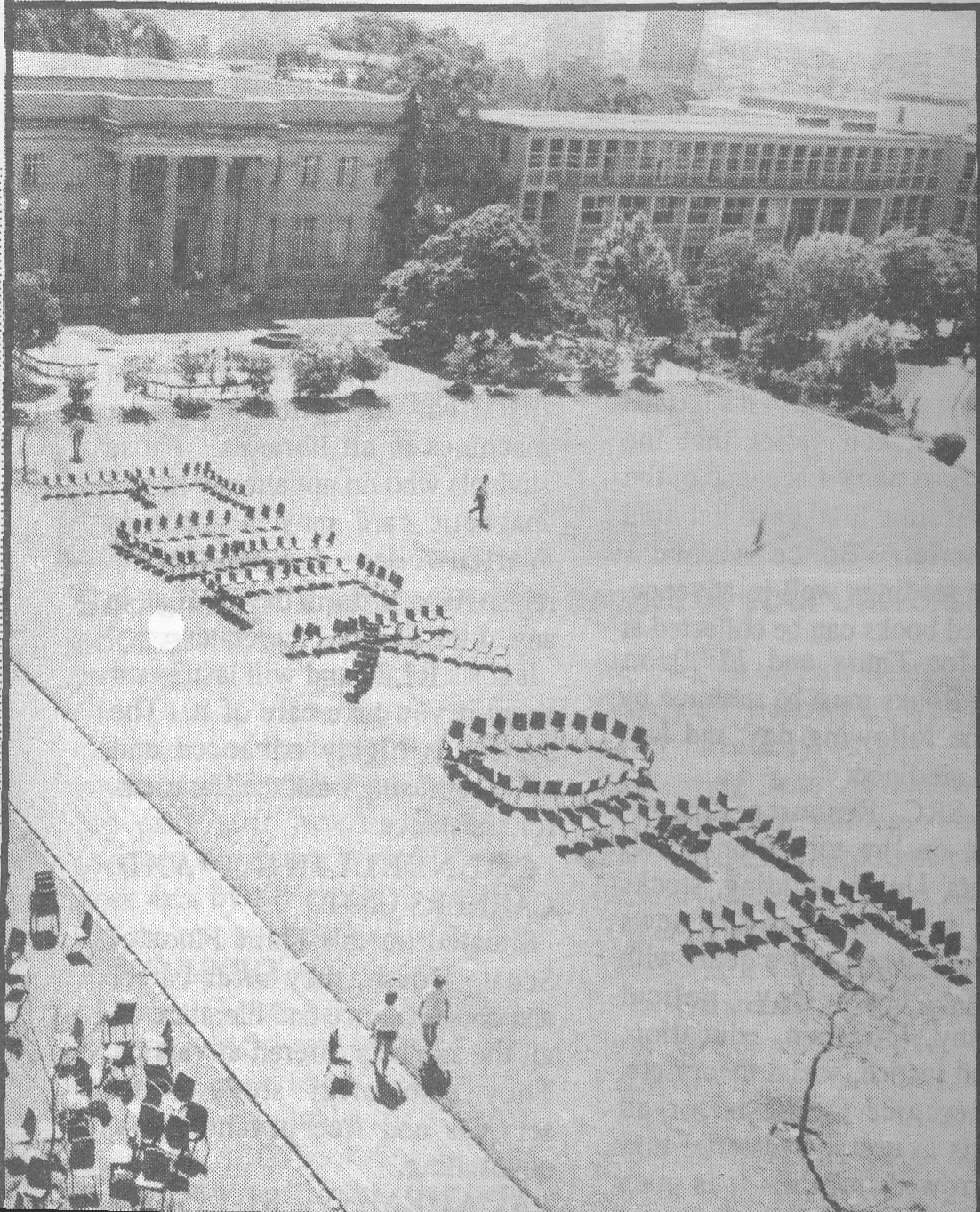

During

apartheid, the South African Minister of Education proposed

draconian measures that limited our academic freedoms at The

University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. There were many

small protests. In order to more effectively protest the

restrictions proposed by the Minister of Education, a bigger event

was planned for the lawn in the center of campus. A stage was

erected, and chairs were arranged so that students and faculty could

listen to speeches decrying the Minister’s move. This was to be

followed by a march around the university, which the authorities had

declared illegal.

On the day of the event, the speeches were as resolute as they were

resounding. The final speech came from my boss in the Department of

Anatomy, Professor Phillip Tobias. He had always been renowned as a

great orator, and a vocal critic of apartheid, but he surpassed

himself that day. But toward the end of the speech, with Tobias

saying slowly but resolutely that “we are ANGRY,” helicopters of the

apartheid police started flying overhead, in anticipation of the

illegal march. It made it difficult to hear the final evocative

words, and angered the united assembly of students and faculty. But

the sound of the helicopters only magnified the thunderous applause

at the end of the speech.

It took some time to organize the assembly for the march, so my

students and I, standing on the steps of the 'Great Hall,' were

staring up at the helicopters and down at the lawn where we had

listened to the speeches. One of my incensed students suggested that

we send a message to the helicopters by lying down and spelling

something out. We quickly figured out how many people we would need

to write out our message with bodies lying on the ground, and

started recruiting students. This being a fairly strict South

African police regime we proposing to taunt, only a few were willing

to participate, and not enough. So as I gazed to the lawn, I came up

with another plan, and shouted to my students “The chairs! We can

spell it out with the chairs.”

We ran down and got to work, being careful to keep our backs

to the helicopters, lest we be filmed and identified. I was

particularly vulnerable to being identified, being both a foreigner

and wearing my academic robe. But my adrenalin kicked in and off I

went. As a kid in the USA in the 1960s I had been intrigued by the

civil rights and Vietnam war protests, but was too young to

participate, let alone understand. Now was finally my moment, and I

went for it full force. A picture of the message we sent to the

police in the helicopters above is to the left of he screen.

After writing our quaint message, we still had time to join the

illegal march around the university, and ran to join the crowd.

Along one side of the university, as we progressed, the road was

lined with the South African police. About two dozen police aimed

their rifles at the marchers. The students quickly scattered in the

face of the threat, as well they should have. But something got into

me, probably the adrenalin again. Maybe I was brave, maybe I was

stupid, maybe I thought that my academic robe was bullet-proof vest.

Certainly I was incensed, so I stood my ground, crossed my arms, and

glared back at those police and their rifles.

Now you must know that the police had rubber bullets in their guns,

and I knew that. But those can hurt or put an eye out (as our

mothers would have warned us.) Yet to this day I can feel the

determination for academic freedom and fair opportunities for

education that I felt then. I did not get shot, but the story does

not end here.

The students regrouped en masse, in front of the police brigade, and

began singing politically motivated songs. It was a stand off that

lasted roughly half an hour while a university administrator who had

been hit by a rubber bullet on another occasion, negotiated with the

police. It was agreed that we could sing one more song, and the

natural choice was Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. It means “God Bless

Africa,” and was a rallying call for the apartheid resistance

movement; it is now South Africa’s national anthem.

As soon as we started singing, the police broke their agreement and

lobbed tear gas canisters at us. I wasn’t sure whether to be excited

or distressed. Maybe the police on the ground got word of our little

message to the helicopters on the campus lawn?

Whatever the case may have been, what caught my attention was that

suddenly everybody started lighting up cigarettes. Very few had been

smoking up to this point, so it seemed like an odd time to me. But

it turns out that, right or not, there is a belief that smoking

cigarettes helps you open up your lung passage ways when you’ve

inhaled tear gas. So somebody gave me a cigarette, and I once again

joined the behavior of the crowd. It didn’t hurt, that’s for sure.

The lessons I learned that day were these:

Never be afraid to stand up for your convictions, and always take a

pack of cigarettes to a protest that might involve tear gas. As time

went by, however, I learned a greater lesson. Yes, one must stand by

one’s convictions, but one must always be open to reexamining them.

Such was the case with that notorious Minister of Education who

tried to impose apartheid restrictions on our university. He later

became president of South Africa, and, with an apparent change of

heart, went on to set the stage for the end of apartheid. He freed

apartheid resistance leader Nelson Mandela from prison, and

eventually shared the Nobel Peace prize with Mandela. His name was

F.W. de Klerk.

www.riddledchain.org